★ Win a Schöffel Country shooting coat for everyone in your syndicate worth up to £6,000! Enter here ★

New barrel, new horizons

The project rifle has produced good results with its factory barrel, but a change is afoot in order to push the limits further

By now Project RS has had a few rounds put through its barrel, so we decided to take out the bore scope to have a closer look. Now if you haven’t looked up the tube of your pride and joy before, be warned: it looks bad to the untrained eye, even on a relatively fresh barrel. The combination of 55,000+ psi of pressure forcing a copper-jacketed bullet up the tight bore will always leave traces of carbon and copper.

Depending on the type of manufacturing process used to produce it, the internal finish will dictate how much copper will be retained. A cut rifled barrel will copper up less and clean very easily compared to a hammer-forged barrel, as used in most production rifles.

What the barrel can be made of is also up to the barrel-maker to choose; it could be a chrome-moly steel such as 4140 or a stainless steel such as type 416. The important characteristics of the steel are how machinable it is, its longevity and its overall strength. Other considerations include its ability to be blued and resistance to corrosion. Stainless steel barrels make up almost 100% of the barrels we fit, as the grades of stainless steel used for barrels are fairly machinable and offer a long accuracy life. They are also more resistant to some of the modern ammonia-based cleaners used by some shooters.

The .243 Win must be one of the most popular calibres here in the UK because its versatility is pretty much unmatched by any other calibre. Its main role here is a round used mostly for killing the smaller species of deer and in fox control. Interestingly it was first developed 1955 as a varminting round based on a necked-down .308 Win.

Since the UK Deer Act of 1963 – specifying a minimum bullet diameter of .240” as well as minimum levels of muzzle velocity and bullet energy – the .243 is now looked at as THE entry-level calibre for deer control, at least prior to legislation changes concerning muntjac and Chinese water deer. In my view it is still a terrific all-rounder.

Project RS started life as the popular .243 but has now been changed into its ‘Ackley Improved’ big brother. With less body taper and 40 deg shoulder, its case capacity is increased by 7-8%, giving a useful increase in velocity and better case life due to the sharper-angled shoulder resisting the brass migrating forward over the lifetime of the case, meaning less trimming for length and the shoulder of the case needing to be bumped back less.

A lot of people are put off by the PO Ackley offerings due to the need for fire forming the case in the ‘improved’ chamber to produce the Ackley case. This is true, but if you are into your accurate reloading then until the new case has been fired in your chamber it really isn’t going to give the best results in terms of accuracy. I often recommend clients buy quality factory ammo to use through their new barrel so there is no waste in barrel life ‘fireforming’ cases; just zero and use the factory ammo as normal, then when fired through the improved chamber you are left with an Ackley Improved case.

So, after some discussion, it was decided to fit the T3 RS with a barrel that was better spec’d to shoot the heavier bullets so that Dom could stretch its legs and utilise the ‘dial-ability’ of the Nightforce NXS scope.

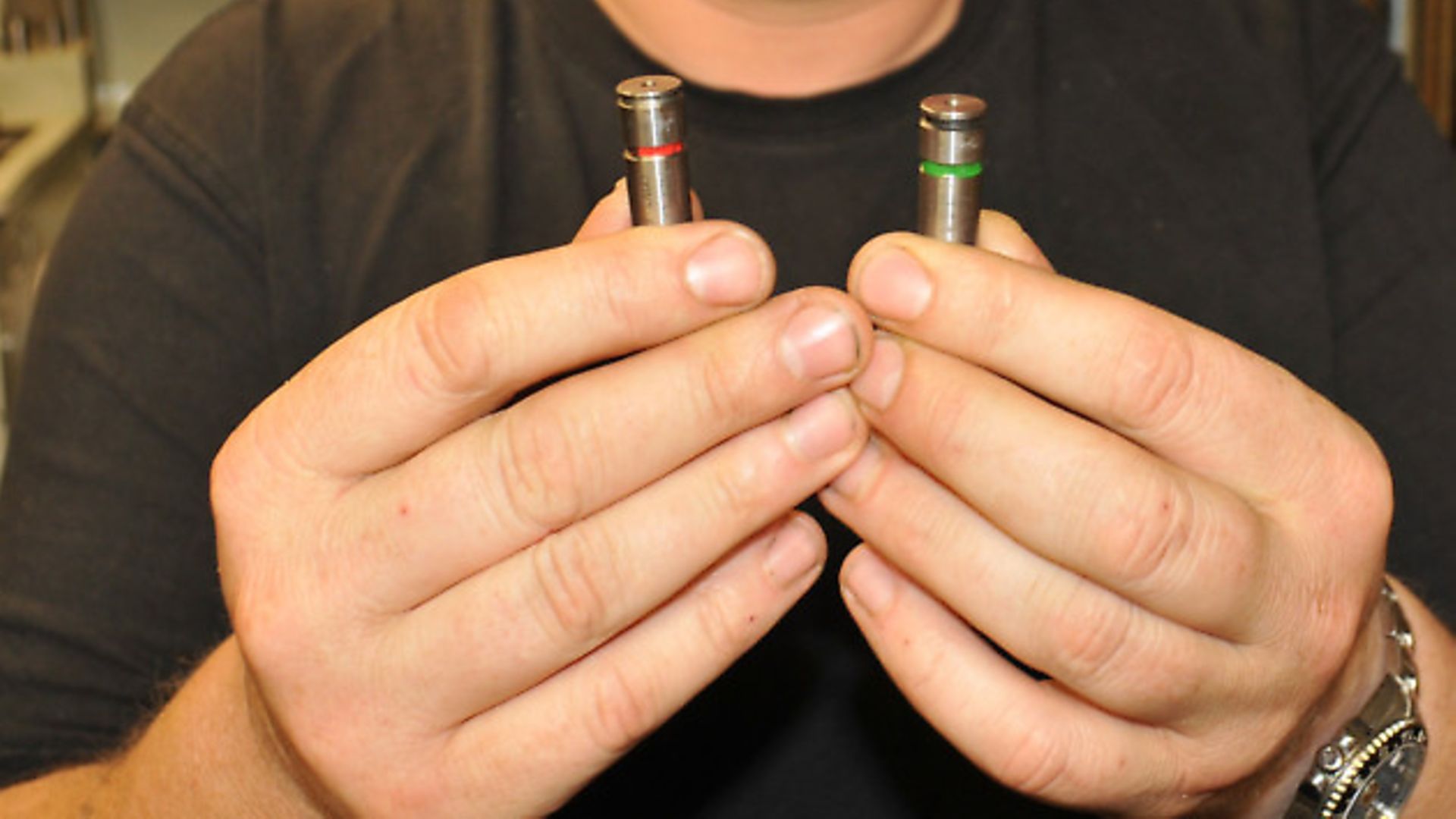

We chose a Shilen Light Varmint profile with a 1 in 8” twist for the job. With the correct bushing selected for the reamer to give a perfect fit in the bore, the chamber reamer will track precisely to produce an accurate chamber that is 100% true to the centre line of the bore. This, in my opinion, is the most singularly important factor in producing an accurate rifle.

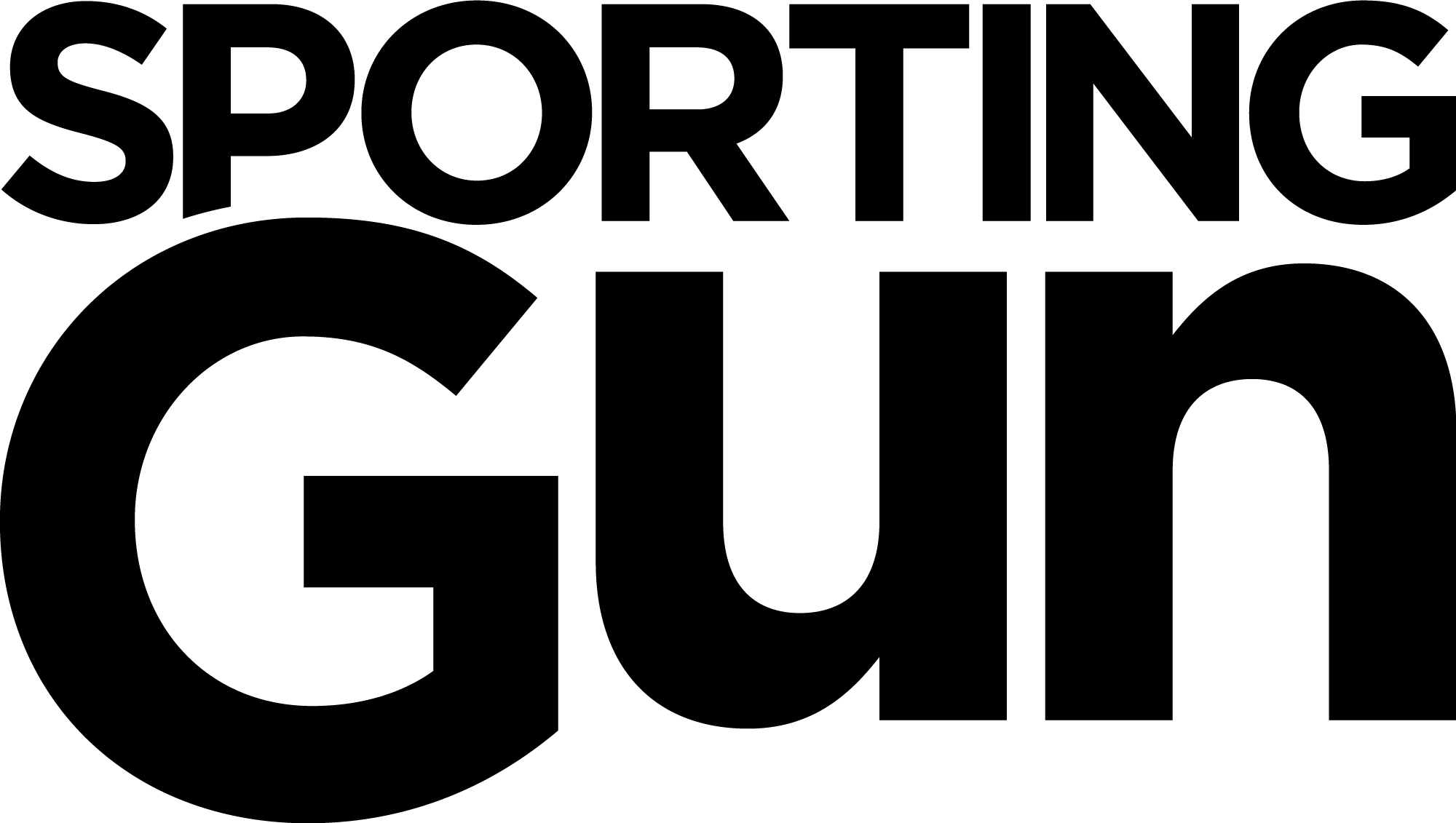

The barrel now dialled in the lathe, we cut the tenon ready to accept the threads for it to mate with the action. This interface between the barrel and the action is simply the same set-up as a very tight tolerance nut and bolt; they screw together. The tenon has a shoulder that the barrel butts up against the action and which is perpendicular to the bore.

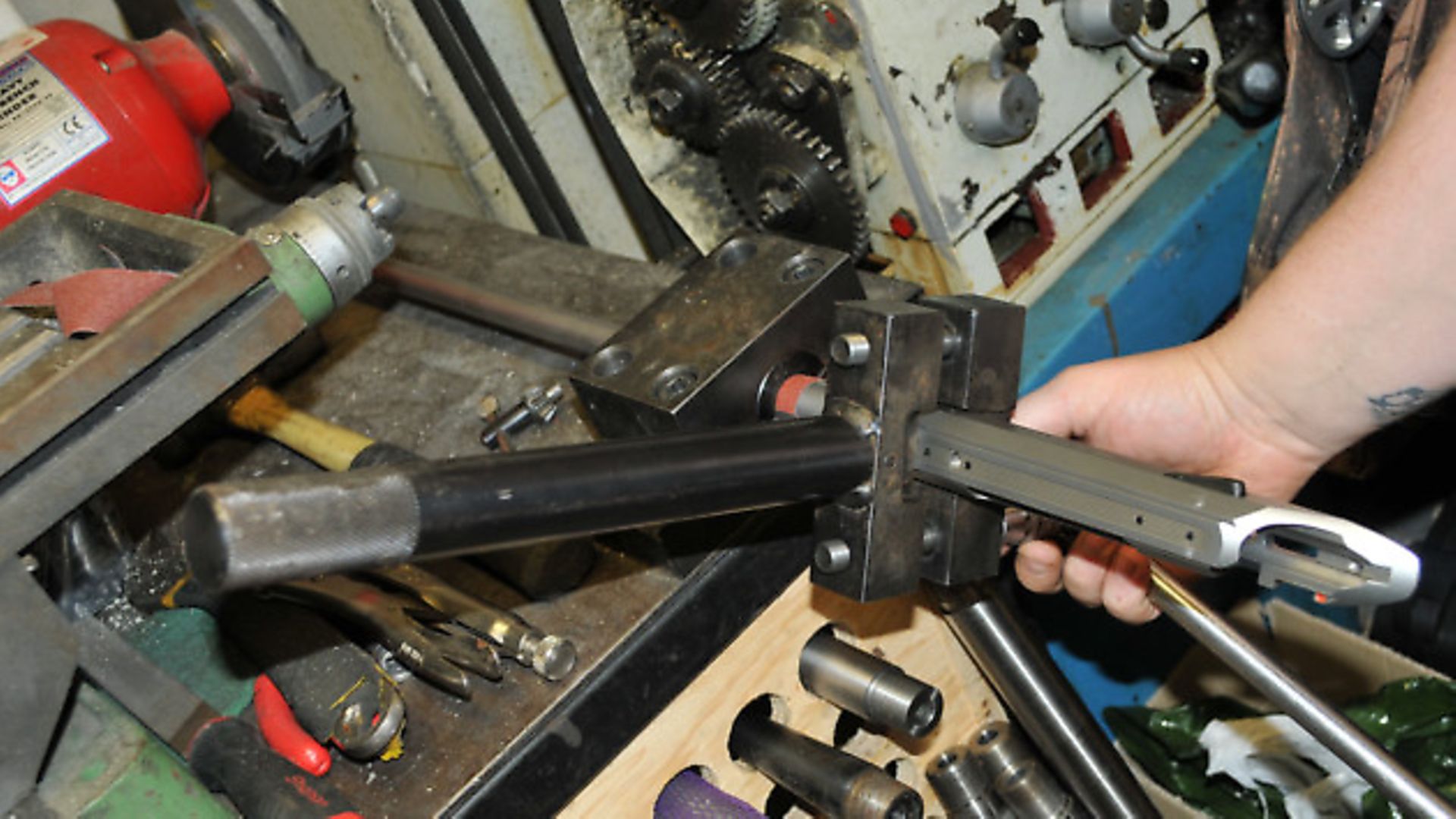

The chamber is then cut with the correct finishing reamer to a headspace tolerance of a max .004”, but as a rule and with project RS using .243 Ack go and no-go gauges, we set it up so the bolt shuts nicely on the go gauge and with .001” shim on the back of the go-gauge it won’t shut. This a simplified account of what goes into the job of fitting a barrel. It’s a subject that I find very interesting and on which I could write several thousand words and still want to add some to this article.

With the work complete on the chamber end of the barrel, we have a look up the barrel with the bore scope to check for any irregularities: it looks good! All that is left to do is reverse it so we can run a thread and crown to finish the job.

The barrel is then fitted to the action with some assembly lube as the new stainless threads working against the stainless steel action can gall making everything lock up/seize together during assembly.

When working with similar materials such as stainless steel in tight tolerances, running dry threads is a big no-no. The new barrel is screwed onto the action and torqued up then all that is left to do is make sure it fits in the barrel channel with no contact forward of the action face to make it truly free-floating. Fortunately the GRS stock gives plenty of space for heavier barrel profiles and gives good clearance. The barrel in its free-floating state acts like a tuning fork, in that every time it is fired it moves at a known frequency because it is being held exactly the same every time. If the barrel touches the fore-end inconsistently the frequency will change and you won’t get perfectly repeatable results.

We grab some new Lapua .243 cases and Sierra bullets and put together a few test rounds just to check the chamber has no marks in it that would imprint themselves onto the case.

I ask Dom to put a few of shots down the ‘firing hole’. He looks slightly nervous at the prospect of firing a few rounds into the hole but it’s no problem; he mans up and manages to get most of them on target…

Once fired I inspect the cases. Everything looks good, so we give the new barrel a good clean and inspect again: it’s all rosy! Next stop is the proof house.

By Chris Blackburn of UK Gunworks

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Sporting Gun

Subscribe to Sporting Gun magazine and immerse yourself in the world of clay, game and rough shooting. As the leading monthly publication for passionate shooters at all levels, Sporting Gun delivers expert advice, practical tips and in-depth reviews to enhance your skills and enjoyment of the sport.

With features ranging from gundog training to pigeon shooting, and wildfowling to equipment recommendations, you’ll gain valuable insights from professional shooters and industry experts. A subscription not only saves you money on the cover price but also includes £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering the use of shotguns, rifles and airguns for both recreational and professional use.