★ Win a Schöffel Country shooting coat for everyone in your syndicate worth up to £6,000! Enter here ★

Why we miss

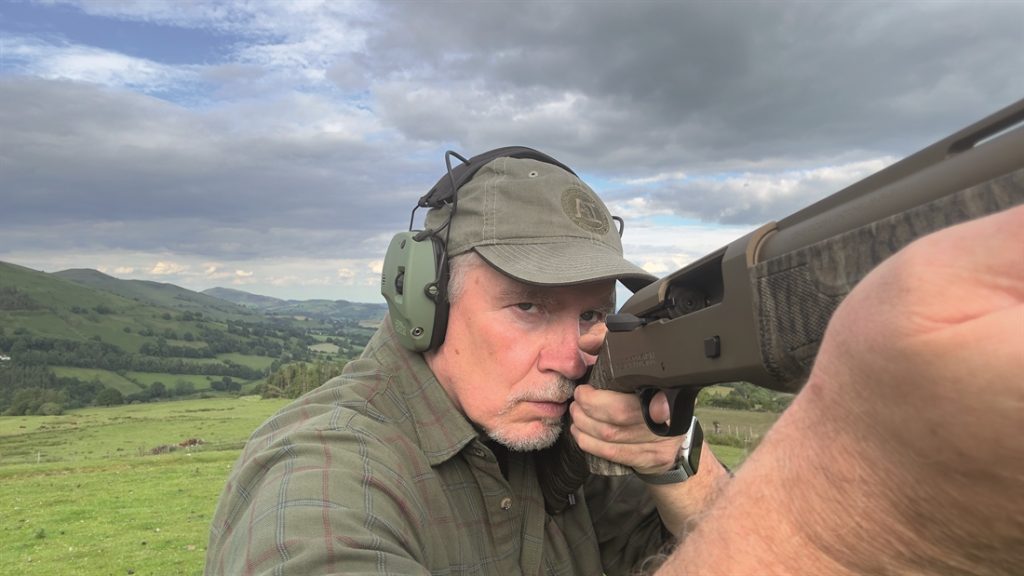

Mike Yardley delves into the key techniques to maintain a smooth and uninterrupted swing and avoid common mistakes in pheasant shooting.

We all miss pheasants but some miss more than others. Why? Well, usually the mistakes are pretty simple ones, we stop the gun, we taken our focus off the bird and bring it back to the gun, we don’t get the forward allowance right misjudging distance, we come off line, we lose balance. These are the main ‘sins’! There are quite a few more, but without getting too complicated lets explore some of the basics in a little more detail starting with gun movement.

Don’t check!! Of all the mistakes when shooting driven game stopping the gun mid swing is the number one cause of misses in my opinion. When I look at my own shooting and that of other sportsmen, checking or hesitation allows more pheasants and other quarry to fly on than just about anything else. I am not alone in this opinion, Lord Ripon noted in King Edward VII as a Sportsman (Longmans, 1911): I will conclude these few remarks on the technique of shooting…with my favourite maxim: “aim high, keep the gun moving, and never check.”

Gun fit may impact on this as can technique. I have noted that too long a stock can check the swing, as can a far forward hold on the forend, head raising, and a failure to lift the gun well with the front hand and push through as the shot is completed. You must also develop a stance which is comfortable and which allows you to keep moving on easily. For driven birds, for this reason, I favour keeping the feet quite close together, and, I move them whenever possible to facilitate the shot. Following through along the bird’s line is also vitally important after you have pulled the trigger.

Stare the bird to death!! In my book, the second, big sin, often related to the first, is failing to keep one’s eye or eyes locked onto the bird’s head though out the entire process of shooting. The importance of developing this skill – and it is nothing else – cannot be over-stressed. To SUSTAIN FOCUS requires developed eye muscles and awareness of the importance of uninterrupted fine focus throughout the shot (the eyes must not come back to the gun). Don’t think it’s natural either. Instinctively we take our focus to a moving object, assess it’s potential threat, and soften focus). To do anything else requires training and practice.

Here is the bottom line. One must strive to achieve and maintain fine focus locked onto the bird thoughout the three seconds or so it usually takes to shoot a bird. And one needs to do this every time. If you do, if you use your eyes well locking on to the head of the bird, it will unlock phenomenal powers of natural hand to eye co-ordination. If you don’t, the swing will become hesitant and jerky, and, the wrong eye may take over too if you shoot with both eyes open (all the more likely if your stock comb is a bit low). Poor focus discipline may also raise your head as noted which will cause the gun to rise and stop.

Now we come onto forward allowance – lead – shooting at where the birds is going rather than where it is. It’s the key skill, safety apart, in shotgun marksmanship. Many shooters simply have insufficient experience of the sheer range of lead pictures required for different shooting situations. I often get people coming to lessons trying to shoot all birds with the same lead, not realising that a pheasant might need anything from a couple of feet at the bird (if you are thinking in inches you are probably looking at the barrel) to 3,4 or even 5 yards for screamers in the stratosphere (which should be left until you have the skill to shoot them – normal mortals should not engage birds beyond 35-40 yards).

This begs a question, moreover. Should one be looking for a measured lead distance deliberately on each shot? The answer is no. Usually, I prefer to take my muzzles to the tail feathers and push on instinctively. If the bird is high, I like to start a yard or two back from the bird rather than on the tail feathers. But, in all cases, I like to form some sort of muzzle-bird relationship with the selected quarry early in the process of shooting at it. I note many poor shots never achieve a muzzle-bird relationship initially.

If I look for a lead picture deliberately, as I do on occasion – for example when wildfowling – I keep in mind that a typical bird 40 yards away wants about 6-8 feet or thereabouts. I do not, generally, look for a lead deliberately, just as I do not routinely maintain a deliberate lead. A more natural approach to lead, based, however, on well practised drills with regard to initial muzzle placement, seems to work better for me in most situations. My favoured method now, especially for teaching, is to start the muzzles behind the bird about as far as one want to go in front. So, for an average good bird 30 something yards up, I’d start on line a couple of yards behind the bird to go a couple of yards in front.

Mention of this new method (which I have developed as refinement of the classic ‘swing-through’ technique’) brings us on to the subject of line. Keeping on line is just as important as getting the lead right. Although errors of lead are common on the shooting field, misjudging a bird’s line is a frequent cause of missing as well. This is an interesting topic because it is often said by sophisticated shooters – ask the boys at West London or Hollands – that line is as important as lead, but, equally, one often hear’s the dictum repeated: “don’t cant” – i.e don’t twist the gun relative to the line of the bird.

This requires a bit of thought and explanation, because it all depends on how you look at it. It is big mistake to cant the gun relative to the bird’s line. But, I frequently make an adjustment by twisting, i.e. canting, the gun to help follow its line. Give it a little thought in your mind’s eye (or better still, get out a proven empty gun and practise some of the basis movements).

In simple terms, driven birds coming to you may be shot without any noticeable angling of the barrels within a certain arc to one’s immediate front – but, this arc it is quite tight – perhaps no more than 5 degrees to either side of centre. As soon as the bird moves significantly to the right or left, you should adjust your barrels to match the line of the bird. For a right-hander a bird to the right may require a slight anti-clockwise rotation, a bird to the left, a clockwise one. Here is the easy way to understand it. In the case of a side by side the barrels – a line drawn through the centre of the muzzles – need to be parallel to the bird’s line and the barrels of an over an under need to be perpendicular. This is an active process. I sometimes call it ‘squaring up’. Another way of explained it is that the shoulders should remain level with the line of the bird.

As noted, many birds are missed because the range of them is misjudged. Let’s keep it simple: frequently, the height of pheasants is over estimated – which may cause misses in front as well as a tendency to lose or fail to achieve any sort of adequate muzzle quarry relationship initially. Strangely, it is also the case – and I have watched it often on clays simulating game as I have on live game – that many close, and apparently easy “I-wouldn’t-bother-raising-my-gun-to-that birds” are missed in front too. I have noticed this on numerous occasions when I have been standing on a peg with others. I shall not pass further judgement on the sporting ethics though – other than to say a proper sportsman only shoots those birds which are worthy of a shot, he leaves birds which present no challenge.

So often in the shooting press you see pictures of people shooting who are completely out of balance. Some, indeed, look as if they are about to fall over!! Good shots usually have great gun mounts and good footwork too – they co-ordinate their lower body movements with the mount and swing. They take delicate little steps, barrels and front foot moving together when required, and, they don’t get wrong footed easily. We all do sometimes, of course (especially in soft plough) and, when it happens we end up shooting poorly. When I pull the trigger, I want to have my rear foot at about 90 degrees to bird. If you can’t move the feet, tension is introduced into the swing and missing behind and offline becomes all too probable. Extending the front hand may also introduce tension in the swing though it used to be a fashion.

If you look at the typical pics of driven game shooters, you will note that those who are in perfect balance at the moment the shot is taken are definitely in the minority! The simple rule is keep the front shoulder over the front foot – but it is easier said than done in a hot corner. One thing that I find helpful is to take some fast, unexpected, shots to the right by bringing my weight deliberately onto the right foot – not something I would normally do or advise for right-handers. This is an adaption of Mr Churchill’s technique. Though I am normally a Stanbury man (that great instructor had a beautiful stance but he never discussed moving the feet much in his once extremely popular books with Gordon Carlisle).

Great shots have great timing. They never seem to lose it. For most, though, everything may go like clockwork on occasion but all too often the wheels wheels fall off. It is an interesting subject and not as complicated as one might think. I teach my shooting students to become consciously aware of their timing. Most people who shoot well, shoot to three beats – One: Two: Threeeeeee. Tempos change depending on the range, angle and speed of birds, but we should never lose that lovely, elegant, three beat time: ONE:TWO:THREEEEEEEEEEEEE not poke and hope! Good timing helps the follow through. It develops economy of movement and rarely looks rushed.

Just as many over think mid swing – often neurotically considering lead in inches when their focus mental and physical should be on the bird, many miss because they tense up. Overthinking and physical tension are related sins. To shoot well, one wants to be bodily relaxed but positive of mind. One must commit to every safe shot, and, once committed, shoot decisively. Good shots really want to get their birds and can beat themselves up when they miss. I don’t advocate that you do the latter, but do maintain a positive mindset – you won’t be able to suppress all nerves, but you can use them in your favour. And, remember the effect of anxiety is to disrupt focus and smooth movement. Concentrate on these and you are more than half way to conquering your mind as well. I” say that again, to succeed concentrate on sustained, locked-on focus and smooth movement. As one friend put it in jest every shot “smooth as wiesel sh_t!”

If you start to get flustered because you are missing, you will create a viscous circle becoming more tense and anxious. Flow will disappear from your shooting. The antidote is to relax and go back to essentials: muzzles to the tail feathers or as required, push on, keep focussed on the head or beak. Keep pushing through smoooooooothly. THE GUN MUST KEEP MOVING AFTER YOU HAVE PULLED THE TRIGGER.

Finally, some miss birds because they are under (or, indeed, sometimes over) gunned. In recent years, I have increased my payloads significantly (32 grams in my norm) and gone up a pellets size (to 5 shot for most of my driven shooting). On tall birds, big pellets in larger number and a bit of choke definitely help.

I have managed to get this far without mentioned two of my favourite subjects much – eye dominance and gun-fit. It should go without saying that anyone with common sense who shoots regularly should be aware of the need for a occasion confirmatory checks of eye dominance and gunfit. A stock which is slightly too high, meantime, is much better to a game shot than one that is slightly too low (which may cause the wrong eye to take over in some circumstances). To check yours, take a proven empty gun and mount it skywards at about 45 degrees. If with normal cheek pressure you can’t see the bead, the stock is probably too low. You should (unless their has been deliberate adjustment to compensate for eye issues) be looking down the centre of the rib too. My last words? I shall repeat myself again unashamedly: keep the weight over the front foot, keep the head down, stare each bird to death and keep the gun moving and on line after you have pulled the trigger… don’t rush to a stop.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Sporting Gun

Subscribe to Sporting Gun magazine and immerse yourself in the world of clay, game and rough shooting. As the leading monthly publication for passionate shooters at all levels, Sporting Gun delivers expert advice, practical tips and in-depth reviews to enhance your skills and enjoyment of the sport.

With features ranging from gundog training to pigeon shooting, and wildfowling to equipment recommendations, you’ll gain valuable insights from professional shooters and industry experts. A subscription not only saves you money on the cover price but also includes £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering the use of shotguns, rifles and airguns for both recreational and professional use.