Guns at auction

Guns at auction might seem like bargains, but hidden costs and unforeseen repairs can quickly add up, says Diggory Hadoke. Take care to avoid unexpected expense.

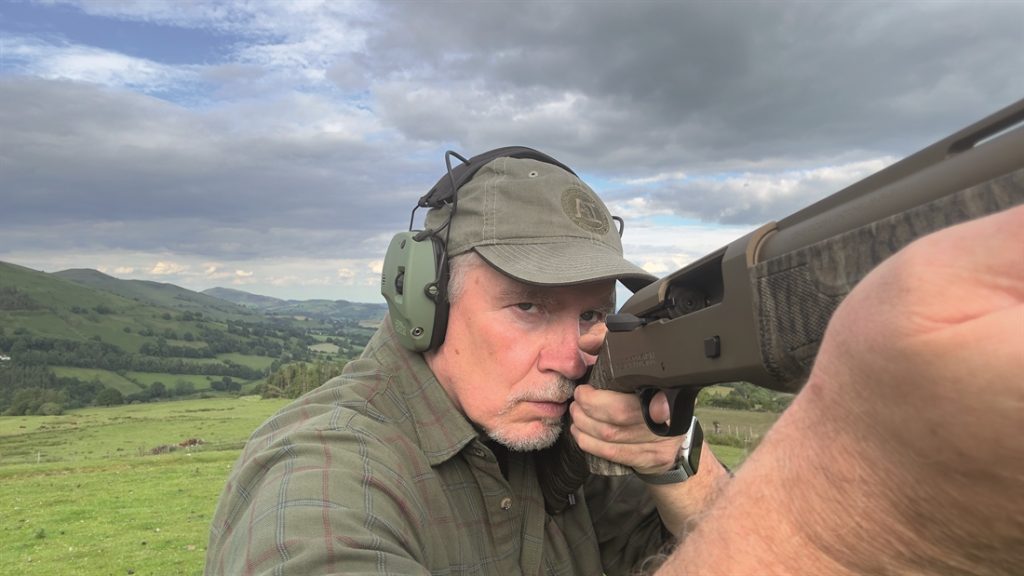

I have been frequenting gun auctions since the late 1990s and writing about them since 2003. Over those two decades much has changed. It used to be accepted that attendance at the viewing days and the auction day itself was essential. Catalogues were sparsely illustrated and descriptions were deliberately brief. Much sold at auction was unsuitable for the general public. The auction was largely the preserve of the trade and some specialist collectors, who invariably had assistance from a trusted expert. The internet did not have much infl uence on auctions in the early 2000s. However, it has since transformed them. Today, nicely photographed and described guns appear on the websites of every auctioneer, along with bore dimensions, minimum wall thicknesses, age of the gun, provenance and other facts. Buyers who once recoiled from the idea of bidding on a gun that they had not personally and closely inspected now routinely bid thousands of pounds on guns they have seen merely as online images. In short, auctions have become internet-driven retail environments. Online shopping is the modern way.

Buyer beware

A question I am often asked is: “Should I buy at auction, where the prices seem a lot lower than they do in my local gunshop?” My fi rst response is the age-old cliché that governs buying at auction: buyer beware. Unlike a retail environment, where the seller has a duty to the customer to sell something fi t for purpose and with some expectation that it will work and be reliable, auctions sell everything ‘as seen’. You see it, you bid what you think it is worth. If you win the lot, you bought what you saw. If it turns out to be no good, that’s your misfortune. As long as the description was not an outright lie, you are stuck with it.

In practice, if the auctioneer says the gun has 25in barrels and it turns out to have 24in barrels, you can claim misrepresentation. If it has the described 25in barrels but you later fi nd out they were shortened from 30in and the gun patterns really badly, bad luck. There is no comeback. If the gun has a single trigger and it doesn’t really work, but you don’t realise it doesn’t work and buy it in ignorance, bad luck. The onus was on you to appraise the gun, not on the auctioneer to test and vouch for its functionality.

Essentially, the auctioneer is merely an agent to facilitate the sale of an item, for which he takes a fee. He is not a vendor himself. This might seem unfair, given the modern expectation for unquestioned returns policies and generous consumer rights. However, auctions are traditionally where the trade buys items unsuited to retail in their current state. That is why they are often ‘cheap’. A gun that to a professional might be a money-earner if he applies his specialised knowledge to restoring it, is merely a gun that doesn’t work to a layman.

Still, the lure of those prices is strong. The headline ‘sold’ figures in past catalogues look so tempting. Sportsmen seeing a photo of a nice sidelock with a very low price next to it assume it is just as good as the one in the local gunshop at three times the figure. It almost never is.

A quality British gun can comfortably last four or five generations of shooting if reasonably well cared for. However, 100-year-old guns have been around long enough to experience wear, neglect, abuse and poor maintenance. This isn’t always the case but it quite often is – and if it’s brilliant, why is up for sale? They say fine horses never hit the yard.

Barrel condition is one reason many good-looking guns are in auctions rather than gun shops. A photo cannot tell you how enlarged the bores are. Nor can it tell you how thin the barrel walls are. When you consider the cost of a new set of barrels from Purdey is over £30,000, it becomes obvious that barrel condition is a huge factor in determining the value of a used one.

Added expense

The cost of gunsmithing is also a consideration. Many guns in auction will not have been ‘prepared for sale’. They will simply be as they arrived. A proper strip, clean, service and tightening to a loose gun can run to £300. If the rib is loose, add £300 and the same again to reblack the barrels once the work is done. An apparently minor issue with ejector timing could be a badly repaired limb that requires new parts. An intermittently non-firing single-trigger could just be worn out. Ejectors and single-triggers can be money pits to engage with.

Remember, many guns like this, with problems the professionals have uneconomic to continue trying to repair, are put into auction as a means of disposal.

So far, for an article on buying guns at auction, this piece might appear more like a warning not to. But it is important to make clear the pitfalls. It is certainly possible to buy very good guns at auction, sometimes at a lesser price than you might expect. You just need to learn how to sort the good from the bad. To be successful you need knowledge, or a person with that knowledge to advise you. It is important to know one’s limitations.

Auctioneers have worked hard to make buying a retail experience and often achieve prices that exceed what a retailer would ask. A bidding frenzy on the day can inject momentum and that can inflate prices, especially when you add the buyer’s premium and VAT. The bottom line of your invoice can go up by 30% or more.

Despite the caveats I have listed so far, auctions can be a good source of guns. A big catalogue places a lot of guns on the table to be sold at one time and there are often things worth having at prices lower than usual. Some important collections are sold through auction houses, so catalogues often contain guns that would never appear in shops.

As well as the prospect of finding and buying some interesting guns, the auction viewing room is a place of education. Rarely will you see such an array in one place and have the chance to handle and inspect them. But be warned. Once you start getting involved in auctions they can become dangerously addictive.