Mindful shooting

Christian Schofield delves into the world of sports psychology to pinpoint how we can find our competitive advantage, and discovers that ‘mindful’ practice could hold the key

Ten years ago, the British Medical Bulletin informed us that the big development in sport was not an increase in the performance required to win, but an increase in the number of athletes capable of winning. This development is evident in both domestic and international shooting competition.

In qualification for the Olympic Trap final at last year’s world championships, 22 men (17% of the field) were within two targets (1.6%) of the qualification score. The question is how can we learn to win in this increasingly competitive environment? Perhaps we should consider the thoughts of Jack Welch, who achieved great things in the complex and competitive environment of business: “Your ability to learn, and rapidly translate that learning into action, is the ultimate competitive advantage.”

Reflecting on this situation, two of the great US sports psychologists, Robert Weinberg and Daniel Gould, suggest that our error is to focus on what we currently know and understand rather than looking for new ways to develop. They give examples of athletes trying to eradicate performance mistakes, such as losing concentration and tightening up under pressure, by merely doing more practice.

In response to these findings, coaches and sports psychologists have included psychological skills training in athlete development programmes, the idea being that systematic and consistent practice of mental skills increases enjoyment and enhances performance. To find the right techniques for us, sports psychologist Dr Robin Vealey suggests that we determine how we want to be in competition. To do this effectively, we must challenge our deeply held beliefs and our current behaviours. This can be difficult, as any challenge to our basic assumptions can create anxiety and defensiveness. The theory is supported by research which shows that psychological skills training is less effective when those delivering the training don’t know the athlete well or lack sport-specific knowledge. A generic development programme is, therefore, of little value.

With total absorption in the present cited as the route to exceptional performance, psychologists have sought to help athletes become immersed in their task and enter what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes as ‘the flow state’, a phrase which has a similar meaning to the colloquialism ‘being in the zone’.

However, Professor Claudio Robazza of the University of Padova in Italy, reported that, although highly desirable, the flow state is hard to initiate and difficult to control. He went on to suggest that traditional mental skills programmes, designed to help us achieve an optimal state, are not always effective when we are anxious or tired.

In an alternative approach, Claudio Robazza suggests that we should be aware of our thoughts, emotions and physical feelings, and mindfully accept unpleasant sensations rather than trying to suppress them. When we realise that we are not going to get into the flow state, we should switch to a Plan B by starting to focus on what is described as the ‘core component’. A core component is not necessarily the most important part of our shooting action, but something on which we can focus our attention when we feel stressed or tired. In pistol shooting, aiming was seen as a very effective core component.

In the same way, Professor Joan Vickers of the University of Calgary advocates taking greater control of our actions. In experiments with biathlon shooters, she found that focusing on achieving a ‘quiet eye’ in the aiming process helped prevent choking under pressure.

There is now a significant volume of research supporting the idea that when we are stressed or tired it is easier to focus on something positive, rather than trying to block unwanted negative thoughts. The conclusion is that a Plan B action-focused strategy can positively influence our emotional state and help us attain the performance we desire.

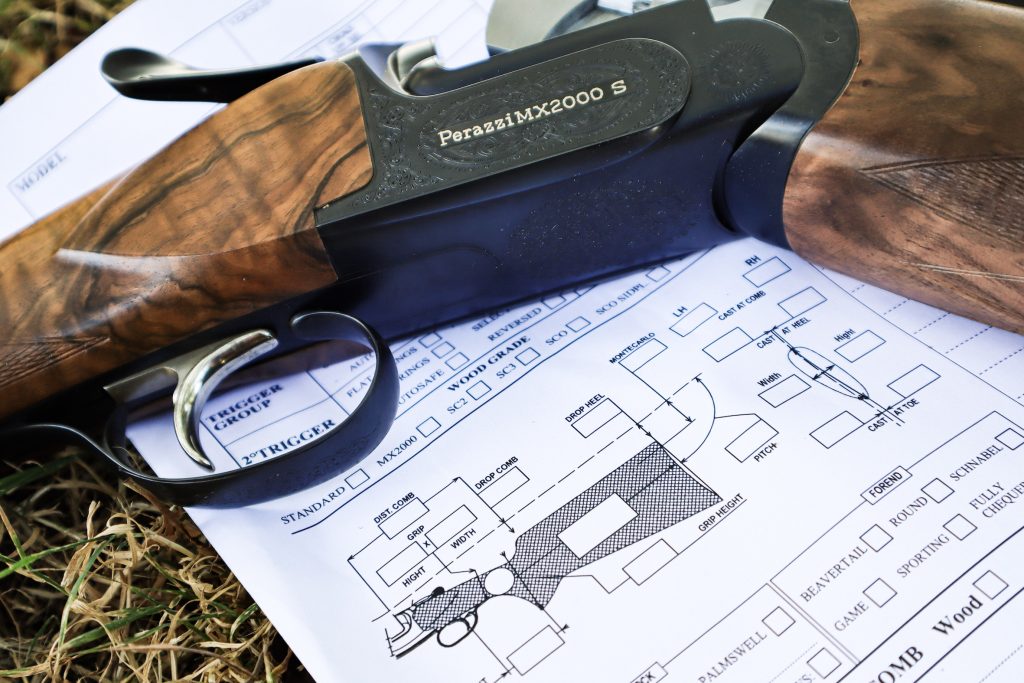

To find the best core component for us, we must be critically self-aware and analyse every aspect of our shooting. A consequence of practice without thinking is that we lose the opportunity to analyse our actions and learn from the experience. To go beyond our current level of expertise requires deliberate effort and a training plan specifically designed to improve performance.

A good plan begins with a clear definition of what we wish to achieve. We should be realistic, as we are likely to lose motivation if our goals are either too demanding or lack a challenge. We should also be aware that support for some psychological interventions can be over-zealous. As one critic has suggested, having a growth mindset will not give us magical powers. However, a growth mindset will allow us to identify learning opportunities that will make a difference.

If learning is achieved through experience we must plan our training, practice and competitions so that we can capture all our thoughts and feelings. In an era of apps and sophisticated diagnostic aids, it may be a surprise to learn that a good tool to help develop self-awareness is a paper notebook. We do not need a sophisticated system. Recording information under these three headings is sufficient:

* What do I want to achieve? (the session or competition plan)

* How did I do? (thoughts and feelings – the outcome in relation to the plan)

* What have I learnt? (what am I going to reinforce, do differently or investigate further?)

Greater self-awareness is the precursor to finding the consistency we require to be competitive in a demanding performance environment. For many, the source of our inconsistency is our ability to remain productively focused on hitting the target.

If we can find a core component to aid the consistency of our focus, we might also find our competitive advantage.