Charlie Portlock gets comfortable in the field

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

When lying in wait for our quarry, we’re forced into making decisions about where to position ourselves so that we have the best field of view whilst remaining unobserved. Sitting or lying comfortably for up to 40 minutes is a challenge for both body and mind and it can be frustrating to have spent time battling with discomfort only to move, startle a pigeon and have to let an area settle all over again.

It’s the law of the earth that wherever we set up, our quarry will always appear from some awkward, untenable angle or behind us, meaning we risk shots from positions that advanced yoga instructors would be proud of.

Being obviously unstable or off-balance will have serious effects upon accuracy, particularly because we haven’t trained ourselves to group well from the supine twist (ask your local guru).

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

The problem is we’re always battling against variables – human, mechanical and environmental. If you shoot a PCP then some of these variables like hold sensitivity can be minimised, but whenever we shoot from any position other than bench rested, our level of fatigue, centre of gravity, breathing, scope magnification and restrictive clothing can reduce our effectiveness.

When you remember a rabbit’s kill zone is the size of a ten-pence piece, one begins to wonder how ethical and humane it is to take shots from unfamiliar positions at a variety of ranges. So I thought I’d see how my groups from field positions compared to my shooting from the bench.

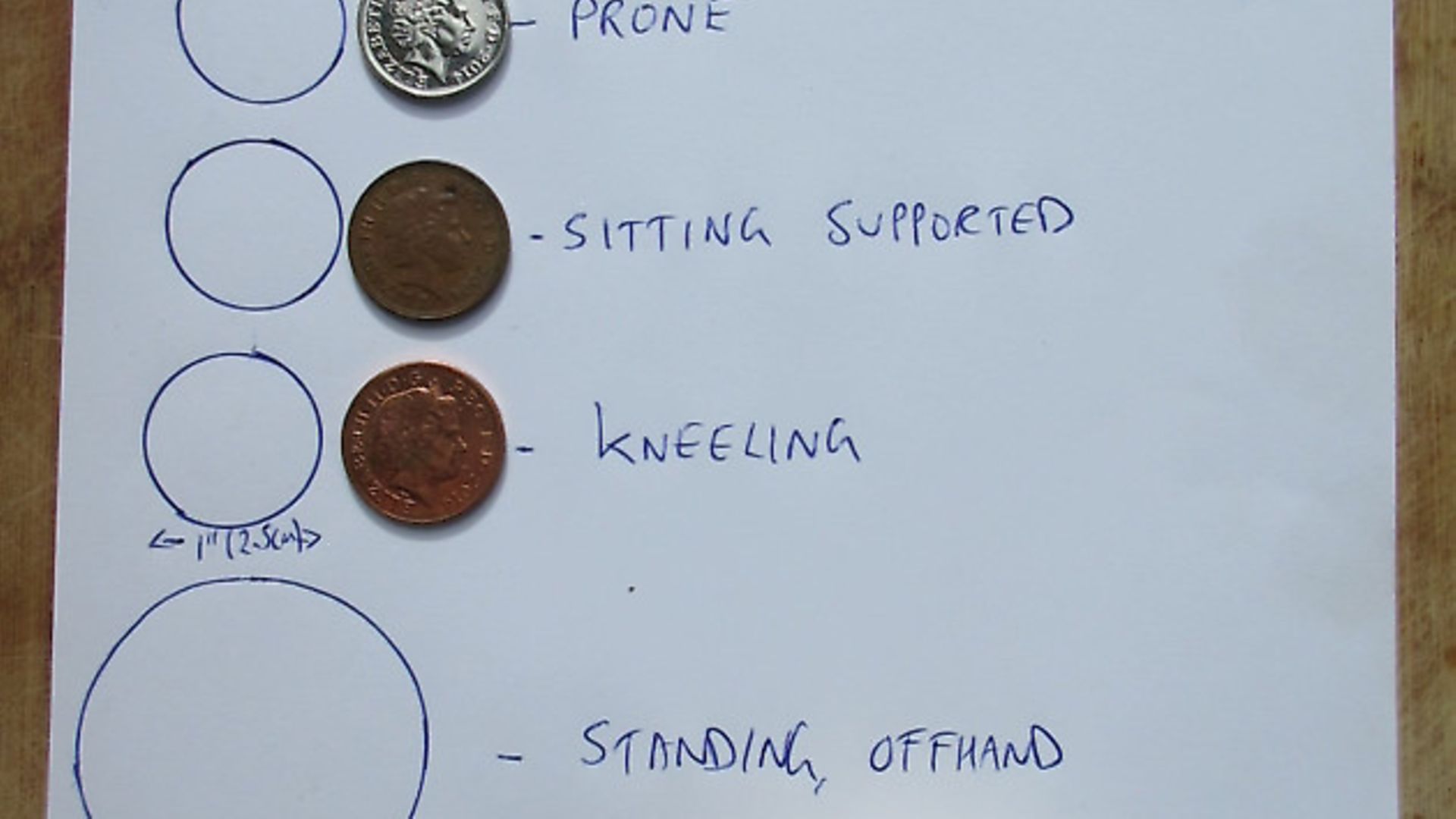

For the test, I shot two groups of five shots from bench rested, prone, sitting (back supported), sitting supported, kneeling and standing offhand. I shot all groups at 25 yards.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

I chose my Sandwell Field Sports tuned 97K in .177 as I’m most familiar with it, but the weight meant I needed to take breaks between groups and sometimes even between shots. For paper, I used Target Air’s excellent pigeon offerings because I felt that traditional roundels weren’t realistic enough, and from all but the standing position, I used the white neck feathers as a point of aim because it was the easiest area to pick out.

Shooting offhand, there was too much scope wobble for a precise POA (point of aim) so I aimed at the middle of the body. This was a fact-finding exercise and I wouldn’t take these shots in the field.

While it’s not easy to replicate real-world hunting conditions when shooting in a controlled environment, there was a breeze, rain, fatigue and frustration aplenty, and I think these factors went some small way to mimic the kinds of mental and physical challenges of shooting consistently in the field.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

I started from bench rested to provide a control group for analysis, and finished with prone. My first two groups from the bench were absolute tosh and it served as a reminder that there’s always some latent physical or mental factors – I call them ‘gremlins’ – that need to be banished before we can come down to the business of focused and accurate shooting.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

The Results

After shooting the 12 different groups from the six positions, it seemed like I’d been fairly inaccurate. My groups looked loose and ragged and because I hadn’t shot at a distinct, fixed kill zone, I felt it was hard to judge just how effective I’d been.

My first group from kneeling featured a string of shots in a diagonal line, which still fell inside a 10-pence piece size group, but I didn’t like the look of them from the perspective of a humane kill. However, I realised that in the field we generally only have one shot and this exercise was not about determining how many pellets I could land in the kill zone, but about finding out how different shooting positions affect real-world accuracy in a more general sense.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Back inside, I covered the largest group with a round object (like a coin) that just concealed every entry point and then compared them with each other beside a grown rabbit’s skull. The skull served as a reminder that even though I was grouping within a ten-pence piece, at the edge of that group was an eye or a cheek. In airgunning, we’re always close to wounding and it’s useful to be reminded of just how close.

I shot my groups in the following order:

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Bench Rested

Not my finest performance, but a solid benchmark with a five-pence piece covering both groups at 25 yards. One hole is what I normally aim for and the 97K can do it.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Sitting (back supported)

This felt very stable and extremely comfortable and although my groups expanded, they still fell within a penny. The perfect position for woodland shooting.

credit: Archant

credit: Archant

Sitting Supported

I lost some confidence here. I’ve always seen this position as my ‘go to’ position as it’s versatile and fairly easy to adopt, but it felt out of balance when compared to the previous position. Although my groups expanded slightly to the size of a two-pence piece, I’d been uncomfortable and using my muscles to compensate for the weight of the rifle. I dialled the scope magnification down to 6x to compensate for scope wobble. The small group size felt like luck rather than ability. I’ll think twice about using the position when others are available.

Kneeling

I rarely use this over sitting, but it felt comfortable even with my right hand unsupported. My groups were better than expected, but still expanded to a two-pence. I’ll be more confident using this position in future.

Standing (offhand)

I was a bit reluctant about this one, especially at 25 yards. Scope wobble was unmanageable at 6x so I settled on a John Darling (4x). My first group was remarkably tight, but my second was about the size of a saucer so I shot a third and it fell somewhere between the two. At just over 2” (5cm) across it wasn’t terrible, but certainly not good enough for hunting. No more standing shots over 20 yards and perhaps none beyond 15.

Prone

I shot this group last because it’s my least favourite position, possibly due to the rigmarole of the reload, reduced visibility and general awkwardness. However, I actually shot quite well by my own standards, with my groups closing back to a ten-pence piece. So much of shooting well lies in being comfortable, and if you have a slightly rising bank in front of you to rest the rifle – on your palm of course – this can be an accurate position if you lack the luxury of a bipod (not a good idea with a springer).

Conclusions

I’d class myself as a no more than an average shot. After all, I had sent three groups of shameful clangers downrange that haven’t gone into print! The rifle is solid and it groups well, but once I’m inserted into the cycle, things become less consistent. As I’ve said, on paper the groups look solid when circled, but more testing is needed to see if that single shot can be made from these positions when it counts, and another life-scale target would be really useful.

If you regularly find yourself shooting form unfamiliar positions then perhaps it’s time to do some in-depth analysis of your shooting, particularity if you’re missing your mark. We can all shoot a couple of pellets at pine cones and get lucky, and this could lure us into thinking we’re better shots than we actually are.

If you’re very confident that you can always make the shot from any position, then why not test yourself on paper? Perhaps some muscles are weaker than others and maybe your set-up has an optimal balance point that’s yet to be discovered.

It’s clear that our groups certainly become larger as we become less stable. Consistent, quick kills are what we all want, and if in doubt then perhaps we should be refusing the shot or increasing stability. Where ethics are concerned we can never be too accurate, and I know I’ll be thinking twice next time I bend over backwards to take an elevated shot at 25 yards. Stay supple and shoot well.

___________________

You may also like:

How to set up scopes and scope mounts to get the best accuracy

How to gauge wind strength and direction

How to get rid of a bad habit with your shooting technique